According to the United States Department of Transportation’s Bureau of Transportation Statistics, in 2018, U.S. airlines carried 889 million passengers with nearly all of them arriving safely to their destination. Despite the statistical safety of airline travel in general, every single one of those people who got on a plane were provided a thorough demonstration of the safety mechanisms and explanation of what to do in the event of a crash.

Also in 2018, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated that approximately 50,300 Americans were newly infected with hepatitis C. Today, hepatitis C rates continue rising, with new infections occurring primarily in young adults aged 20-39, including persons of reproductive age. In fact, research showed that U.S. rates of maternal HCV infection at delivery increased from 0.8 per 1,000 live births in 2000 to 4.1 in 2015.

Back of the napkin math[1] shows that approximately 1,602 children may have been born infected with the hepatitis C virus – a much higher likelihood than perishing in a plane crash. While this figure is just an estimate, I believe it is close enough for you to get the point. That’s 1,602 children who aren’t guaranteed a speech about their mother’s risk factors; 1,602 children who aren’t handed a pamphlet about what to do in this situation; 1,602 children who don’t know to put their oxygen mask on first (to use the airplane analogy); and yet barely anyone is talking about these children, who are more than just a statistic.

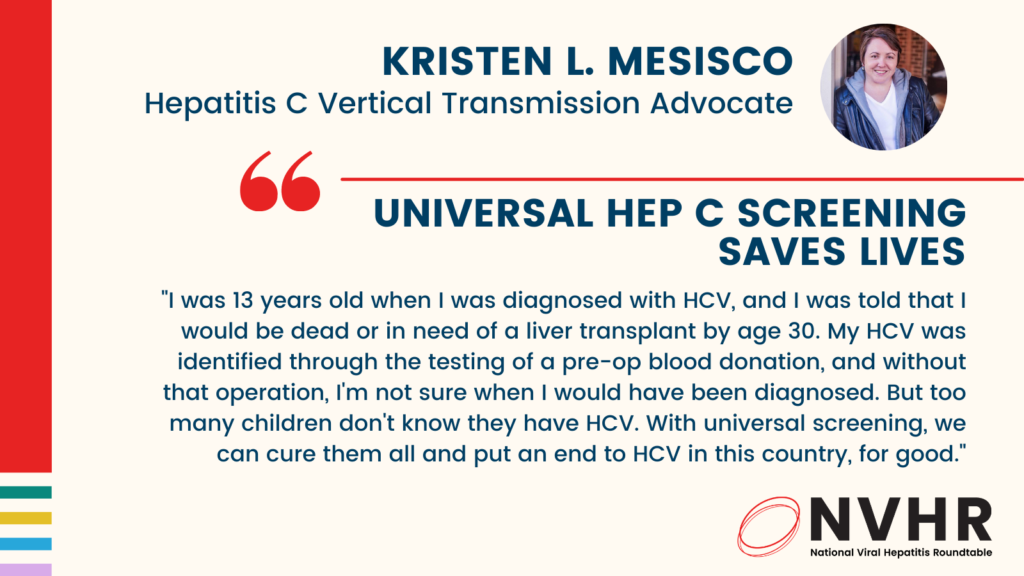

Why does this matter? I am a vertical transmission statistic, meaning I got hepatitis C from my mother at birth, and was 13 years old when I was diagnosed. I was told, rather frankly, that I would be dead or in need of a liver transplant by age 30. I was only diagnosed due to the testing of a pre-op blood donation – or else I wouldn’t have found out. My mother died when I was just 16 months old, and I grew up knowing very little about her and I don’t have any of the other commonly listed “risk factors.” Had I not found out about my HCV, it’s possible that I would have gone on to have children and passed it on to them and so forth. While the chances of vertical transmission are still low, it was a risk I was not willing to take.

I then experienced all the awkwardness of teenage relationships like everyone else, however mine were topped with a coating of confusion, guilt, shame, and the lingering question of who I tell and what will happen if I do. This carried into the ongoing stigma and discrimination that many with HCV experience.

The first time I was blatantly discriminated against because of my HCV status is forever emblazoned in my mind. I was 17 years old and a dental hygienist refused to clean my teeth. I just stood there not knowing what to do. But this stigma carried on well into my adulthood. I went to college for four years and gained a lot of debt, in pursuit of a career that I had wanted for many years. I found out upon graduation that my HCV status was an automatic disqualifier. I then made poor decisions because I was angry that this hepatitis C infection was ruining my life. However, my diagnosis eventually saved my life.

I’m from an area that was especially hard hit by the injection drug use epidemic and could have become yet another statistic. I’ve lost countless friends to overdoses, immediate family members became involved, as did my best friend since kindergarten. But because of my infection that I knew could be transferred by sharing supplies, I refused to inject drugs. Frustratingly, I was often an anomaly among those with HCV as I saw others willingly share needles and works with others, risking the spread of HCV.

Growing up with hepatitis C as a result of vertical transmission was challenging and often without hope. But today, there is a cure, and several treatments are approved for children as young as 3 years old. We now live in a time when the 1,602 kids with possible HCV from vertical transmission don’t have to get sick or carry into adulthood the burden of their parents’ mistakes. Their futures don’t have to be determined by the presence of an antibody in their blood. But for all of this to be a reality, we must find the children who are infected.

Last year, the CDC expanded its screening guidelines to recommend that all US adults get at least one lifetime test for hepatitis C, that pregnant persons are screened with every pregnancy, and that those with risk factors are screened regularly. In addition, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) just updated their hepatitis C screening guidelines to align with the CDC and recommend that pregnant persons are screened during every pregnancy.

These are great first steps, but we can’t stop here. We must ensure that universal screening is fully implemented and that providers, experts, and the public health community come together to develop strategies to make sure no children with hepatitis C go undiagnosed. Together we can put an end to HCV in this country, for good.

Kristen L. Mesisco is a Hepatitis C Vertical Transmission Advocate

[1] Curious how I got that figure? We can estimate that 15,000 of the new infections were persons of childbearing age. U.S. Census data suggests roughly 86% of women will have 2.07 children by the end of their childbearing years. That means roughly 12,900 of those women newly infected in 2016 could give birth to 26,703 children. Current figures suggest that about 6% of infants born to hepatitis C infected mothers in the U.S. are also infected with the virus. That means, because of the women newly infected with hepatitis C in 2016, 1,602 children may have also been born infected with the hepatitis C virus.